Heat shock factors: integrators of cell stress, development and lifespan

Heat shock factors (HSFs) are essential for all organisms to survive exposures to acute stress. They are best known as inducible transcriptional regulators of genes encoding molecular chaperones and other stress proteins. Four members of the HSF family are also important for normal development and lifespan-enhancing pathways, and the repertoire of HSF targets has thus expanded well beyond the heat shock genes. These unexpected observations have uncovered complex layers of post-translational regulation of HSFs that integrate the metabolic state of the cell with stress biology, and in doing so control fundamental aspects of the health of the proteome and ageing.

This is a preview of subscription content, access via your institution

Access options

Subscribe to this journal

Receive 12 print issues and online access

206,07 € per year

only 17,17 € per issue

Buy this article

- Purchase on SpringerLink

- Instant access to full article PDF

Prices may be subject to local taxes which are calculated during checkout

Similar content being viewed by others

Translational reprogramming in response to accumulating stressors ensures critical threshold levels of Hsp90 for mammalian life

Article Open access 21 October 2022

Reprogramming of the transcriptome after heat stress mediates heat hormesis in Caenorhabditis elegans

Article Open access 13 July 2023

Heat-shock proteins: chaperoning DNA repair

Article 20 September 2019

References

- Ritossa, F. A new puffing pattern induced by temperature shock and DNP in Drosophila. Experimentia18, 571–573 (1962). ArticleCASGoogle Scholar

- Lindquist, S. The heat-shock response. Annu. Rev. Biochem.55, 1151–1191 (1986). ArticleCASPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Pelham, H. R. B. A regulatory upstream promoter element in the Drosophila hsp70 heat-shock gene. Cell30, 517–528 (1982). ArticleCASPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Wu, C. Activating protein factor binds in vitro to upstream control sequences in heat shock gene chromatin. Nature311, 81–84 (1984). ArticleCASPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Parker, C. S. & Topol, J. A Drosophila RNA polymerase II transcription factor binds to the regulatory site of an hsp70 gene. Cell37, 273–283 (1984). ArticleCASPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Wu, C. Heat shock transcription factors: structure and regulation. Annu. Rev. Cell Dev. Biol.11, 441–469 (1995). ArticleCASPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Åkerfelt, M., Trouillet, D., Mezger, V. & Sistonen, L. Heat shock factors at a crossroad between stress and development. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci.1113, 15–27 (2007). ArticlePubMedCASGoogle Scholar

- Nover, L. et al. Arabidopsis and the heat stress transcription factor world: how many heat stress transcription factors do we need? Cell Stress Chaperones6, 177–189 (2001). ArticleCASPubMedPubMed CentralGoogle Scholar

- Anckar, J. & Sistonen, L. Heat shock factor 1 as a coordinator of stress and developmental pathways. Adv. Exp. Med. Biol.594, 78–88 (2007). ArticlePubMedGoogle Scholar

- Fujimoto, M. et al. A novel mouse HSF3 has the potential to activate nonclassical heat-shock genes during heat shock. Mol. Biol. Cell21, 106–116 (2010). ArticleCASPubMedPubMed CentralGoogle Scholar

- Powers, E. T., Morimoto, R. I., Dillin, A., Kelly, J. W. & Balch, W. E. Biological and chemical approaches to diseases of proteostasis deficiency. Annu. Rev. Biochem.78, 959–991 (2009). ArticleCASPubMedGoogle Scholar

- McMillan, D. R., Xiao, X., Shao, L., Graves, K. & Benjamin, I. J. Targeted disruption of heat shock transcription factor 1 abolishes thermotolerance and protection against heat-inducible apoptosis. J. Biol. Chem.273, 7523–7528 (1998). ArticleCASPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Xiao, X. et al. HSF1 is required for extra-embryonic development, postnatal growth and protection during inflammatory responses in mice. EMBO J.18, 5943–5952 (1999). Generation of the first HSF-knockout mouse,Hsf1−/−, revealing the physiological function of HSF1. ArticleCASPubMedPubMed CentralGoogle Scholar

- Pirkkala, L., Alastalo, T.-P., Zuo, X., Benjamin, I. J. & Sistonen, L. Disruption of heat shock factor 1 reveals an essential role in the ubiquitin proteolytic pathway. Mol. Cell. Biol.20, 2670–2675 (2000). ArticleCASPubMedPubMed CentralGoogle Scholar

- Zhang, Y., Huang, L., Zhang, J., Moskophidis, D. & Mivechi, N. F. Targeted disruption of hsf1 leads to lack of thermotolerance and defines tissue-specific regulation for stress-inducible Hsp molecular chaperones. J. Cell. Biochem.86, 376–393 (2002). ArticleCASPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Fiorenza, M. T., Farkas, T., Dissing, M., Kolding, D. & Zimarino, V. Complex expression of murine heat shock transcription factors. Nucleic Acids Res.23, 467–474 (1995). ArticleCASPubMedPubMed CentralGoogle Scholar

- Goodson, M. L. & Sarge, K. D. Heat-inducible DNA binding of purified heat shock transcription factor 1. J. Biol. Chem.270, 2447–2450 (1995). ArticleCASPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Larson, J. S., Schuetz, T. J. & Kingston, R. E. In vitro activation of purified human heat shock factor by heat. Biochemistry34, 1902–1911 (1995). ArticleCASPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Zhong, M., Orosz, A. & Wu, C. Direct sensing of heat and oxidation by Drosophila heat shock transcription factor. Mol. Cell2, 101–108 (1998). ArticleCASPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Damberger, F. F., Pelton, J. G., Harrison, C. J., Nelson, H. C. M. & Wemmer, D. E. Solution structure of the DNA-binding domain of the heat shock transcription factor determined by multidimensional heteronuclear magnetic resonance spectroscopy. Protein Sci.3, 1806–1821 (1994). ArticleCASPubMedPubMed CentralGoogle Scholar

- Harrison, C. J., Bohm, A. A. & Nelson, H. C. M. Crystal structure of the DNA binding domain of the heat shock transcription factor. Science263, 224–227 (1994). ArticleCASPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Vuister, G. W. et al. Solution structure of the DNA-binding domain of Drosophila heat shock transcription factor. Nature Struct. Biol.1, 605–614 (1994). ArticleCASPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Littlefield, O. & Nelson, H. C. M. A new use for the 'wing' of the 'winged' helix-turn-helix motif in the HSF-DNA cocrystal. Nature Struct. Biol.6, 464–470 (1999). ArticleCASPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Bulman, A. L., Hubl, S. T. & Nelson, H. C. M. The DNA-binding domain of yeast heat shock transcription factor independently regulates both the N- and C-terminal activation domains. J. Biol. Chem.276, 40254–40262 (2001). ArticleCASPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Sorger, P. K. & Nelson, H. C. M. Trimerization of a yeast transcriptional activator via a coiled-coil motif. Cell59, 807–813 (1989). ArticleCASPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Chen, Y., Barlev, N. A., Westergaard, O. & Jakobsen, B. K. Identification of the C-terminal activator domain in yeast heat shock factor: independent control of transient and sustained transcriptional activity. EMBO J.12, 5007–5018 (1993). ArticleCASPubMedPubMed CentralGoogle Scholar

- Rabindran, S. K., Haroun, R. I., Clos, J., Wisniewski, J. & Wu, C. Regulation of heat shock factor trimer formation: role of a conserved leucine zipper. Science259, 230–234 (1993). ArticleCASPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Nakai, A. et al. HSF4, a new member of the human heat shock factor family which lacks properties of a transcriptional activator. Mol. Cell. Biol.17, 469–481 (1997). ArticleCASPubMedPubMed CentralGoogle Scholar

- Tanabe, M. et al. The mammalian HSF4 gene generates both an activator and a repressor of heat shock genes by alternative splicing. J. Biol. Chem.274, 27845–27856 (1999). ArticleCASPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Nieto-Sotelo, J., Wiederrecht, G., Okuda, A. & Parker, C. S. The yeast heat shock transcription factor contains a transcriptional activation domain whose activity is repressed under nonshock conditions. Cell62, 807–817 (1990). ArticleCASPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Sorger, P. K. Yeast heat shock factor contains separable transient and sustained response transcriptional activators. Cell62, 793–805 (1990). ArticleCASPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Green, M., Schuetz, T. J., Sullivan, E. K. & Kingston, R. E. A heat shock-responsive domain of human HSF1 that regulates transcription activation domain function. Mol. Cell. Biol.15, 3354–3362 (1995). ArticleCASPubMedPubMed CentralGoogle Scholar

- Newton, E. M., Knauf, U., Green, M. & Kingston, R. E. The regulatory domain of human heat shock factor 1 is sufficient to sense heat stress. Mol. Cell. Biol.16, 839–846 (1996). ArticleCASPubMedPubMed CentralGoogle Scholar

- Hensold, J. O., Hunt, C. R., Calderwood, S. K., Housman, D. E. & Kingston, R. E. DNA binding of heat shock factor to the heat shock element is insufficient for transcriptional activation in murine erythroleukemia cells. Mol. Cell. Biol.10, 1600–1608 (1990). CASPubMedPubMed CentralGoogle Scholar

- Jurivich, D. A., Sistonen, L., Kroes, R. A. & Morimoto, R. I. Effect of sodium salicylate on the human heat shock response. Science255, 1243–1245 (1992). ArticleCASPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Shi, Y., Kroeger, P. E. & Morimoto, R. I. The carboxyl-terminal transactivation domain of heat shock factor 1 is negatively regulated and stress responsive. Mol. Cell. Biol.15, 4309–4318 (1995). ArticleCASPubMedPubMed CentralGoogle Scholar

- Zuo, J., Rungger, D. & Voellmy, R. Multiple layers of regulation of human heat shock transcription factor 1. Mol. Cell. Biol.15, 4319–4330 (1995). ArticleCASPubMedPubMed CentralGoogle Scholar

- Holmberg, C. I. et al. Phosphorylation of serine 230 promotes inducible transcriptional activity of heat shock factor 1. EMBO J.20, 3800–3810 (2001). ArticleCASPubMedPubMed CentralGoogle Scholar

- Hietakangas, V. et al. Phosphorylation of serine 303 is a prerequisite for the stress-inducible SUMO modification of heat shock factor 1. Mol. Cell. Biol.23, 2953–2968 (2003). ArticleCASPubMedPubMed CentralGoogle Scholar

- Hietakangas, V. et al. PDSM, a motif for phosphorylation-dependent SUMO modification. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA103, 45–50 (2006). Discovery of a motif for phosphorylation-dependent sumoylation, called PDSM, that is present in the regulatory domain of HSF1 and HSF4.ArticleCASPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Guettouche, T., Boellmann, F., Lane, W. S. & Voellmy, R. Analysis of phosphorylation of human heat shock factor 1 in cells experiencing a stress. BMC Biochem.6, 4 (2005). ArticlePubMedPubMed CentralCASGoogle Scholar

- Westerheide, S. D., Anckar, J., Stevens, S. M., Jr, Sistonen, L. & Morimoto, R. I. Stress-inducible regulation of heat shock factor 1 by the deacetylase SIRT1. Science323, 1063–1066 (2009). Describes the mechanism of SIRT1-mediated deacetylation of HSF1, which maintains HSF1 in a state that is competent for DNA binding.ArticleCASPubMedPubMed CentralGoogle Scholar

- Baler, R., Dahl, G. & Voellmy, R. Activation of human heat shock genes is accompanied by oligomerization, modification, and rapid translocation of heat shock transcription factor HSF1. Mol. Cell. Biol.13, 2486–2496 (1993). CASPubMedPubMed CentralGoogle Scholar

- Sarge, K. D., Murphy, S. P. & Morimoto, R. I. Activation of heat shock gene transcription by heat shock factor 1 involves oligomerization, acquisition of DNA-binding activity, and nuclear localization and can occur in the absence of stress. Mol. Cell. Biol.13, 1392–1407 (1993). CASPubMedPubMed CentralGoogle Scholar

- Ali, A., Bharadwaj, S., O'Carroll, R. & Ovsenek, N. HSP90 interacts with and regulates the activity of heat shock factor 1 in Xenopus oocytes. Mol. Cell. Biol.18, 4949–4960 (1998). ArticleCASPubMedPubMed CentralGoogle Scholar

- Zou, J., Guo, Y., Guettouche, T., Smith, D. F. & Voellmy, R. Repression of heat shock transcription factor HSF1 activation by HSP90 (HSP90 complex) that forms a stress-sensitive complex with HSF1. Cell94, 471–480 (1998). ArticleCASPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Pratt, W. B. & Toft, D. O. Steroid receptor interactions with heat shock protein and immunophilin chaperones. Endocr. Rev.18, 306–360 (1997). CASPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Duina, A. A., Kalton, H. M. & Gaber, R. F. Requirement for Hsp90 and a CyP-40-type cyclophilin in negative regulation of the heat shock response. J. Biol. Chem.273, 18974–18978 (1998). ArticleCASPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Zou, J., Salminen, W. F., Roberts, S. M. & Voellmy, R. Correlation between glutathione oxidation and trimerization of heat shock factor 1, an early step in stress induction of the Hsp response. Cell Stress Chaperones3, 130–141 (1998). ArticleCASPubMedPubMed CentralGoogle Scholar

- Bharadwaj, S., Ali, A. & Ovsenek, N. Multiple components of the HSP90 chaperone complex function in regulation of heat shock factor 1 in vivo. Mol. Cell. Biol.19, 8033–8041 (1999). ArticleCASPubMedPubMed CentralGoogle Scholar

- Guo, Y. et al. Evidence for a mechanism of repression of heat shock factor 1 transcriptional activity by a multichaperone complex. J. Biol. Chem.276, 45791–45799 (2001). ArticleCASPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Shi, Y., Mosser, D. D. & Morimoto, R. I. Molecular chaperones as HSF1-specific transcriptional repressors. Genes Dev.12, 654–666 (1998). ArticleCASPubMedPubMed CentralGoogle Scholar

- Abravaya, K., Myers, M. P., Murphy, S. P. & Morimoto, R. I. The human heat shock protein hsp70 interacts with HSF, the transcription factor that regulates heat shock gene expression. Genes Dev.6, 1153–1164 (1992). ArticleCASPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Baler, R., Welch, W. J. & Voellmy, R. Heat shock gene regulation by nascent polypeptides and denatured proteins: hsp70 as a potential autoregulatory factor. J. Cell Biol.117, 1151–1159 (1992). ArticleCASPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Shamovsky, I., Ivannikov, M., Kandel, E. S., Gershon, D. & Nudler, E. RNA-mediated response to heat shock in mammalian cells. Nature440, 556–560 (2006). ArticleCASPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Chu, B., Soncin, F., Price, B. D., Stevenson, M. A. & Calderwood, S. K. Sequential phosphorylation by mitogen-activated protein kinase and glycogen synthase kinase 3 represses transcriptional activation by heat shock factor-1. J. Biol. Chem.271, 30847–30857 (1996). ArticleCASPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Cotto, J. J., Kline, M. & Morimoto, R. I. Activation of heat shock factor 1 DNA binding precedes stress-induced serine phosphorylation. Evidence for a multistep pathway of regulation. J. Biol. Chem.271, 3355–3358 (1996). ArticleCASPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Kline, M. P. & Morimoto, R. I. Repression of the heat shock factor 1 transcriptional activation domain is modulated by constitutive phosphorylation. Mol. Cell. Biol.17, 2107–2115 (1997). ArticleCASPubMedPubMed CentralGoogle Scholar

- Xia, W., Guo, Y., Vilaboa, N., Zuo, J. & Voellmy, R. Transcriptional activation of heat shock factor HSF1 probed by phosphopeptide analysis of factor 32 P-labeled in vivo. J. Biol. Chem.273, 8749–8755 (1998). ArticleCASPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Collavin, L. et al. Modification of the erythroid transcription factor GATA-1 by SUMO-1. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA101, 8870–8875 (2004). ArticleCASPubMedPubMed CentralGoogle Scholar

- Riquelme, C., Barthel, K. K. & Liu, X. SUMO-1 modification of MEF2A regulates its transcriptional activity. J. Cell. Mol. Med.10, 132–144 (2006). ArticleCASPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Sapetschnig, A. et al. Transcription factor Sp3 is silenced through SUMO modification by PIAS1. EMBO J.21, 5206–5215 (2002). ArticleCASPubMedPubMed CentralGoogle Scholar

- Mohideen, F. et al. A molecular basis for phosphorylation-dependent SUMO conjugation by the E2 UBC9. Nature Struct. Mol. Biol.16, 945–952 (2009). ArticleCASGoogle Scholar

- Andrulis, E. D., Guzman, E., Doring, P., Werner, J. & Lis, J. T. High-resolution localization of Drosophila Spt5 and Spt6 at heat shock genes in vivo: roles in promoter proximal pausing and transcription elongation. Genes Dev.14, 2635–2649 (2000). ArticleCASPubMedPubMed CentralGoogle Scholar

- Yao, J., Munson, K. M., Webb, W. W. & Lis, J. T. Dynamics of heat shock factor association with native gene loci in living cells. Nature442, 1050–1053 (2006). Multi-photon microscopy imaging of polytene nuclei in livingD. melanogastersalivary glands, allowing real-time analysis of HSF recruitment to theHsp70gene. ArticleCASPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Yao, J., Ardehali, M. B., Fecko, C. J., Webb, W. W. & Lis, J. T. Intranuclear distribution and local dynamics of RNA polymerase II during transcription activation. Mol. Cell28, 978–990 (2007). ArticleCASPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Rougvie, A. E. & Lis, J. T. The RNA polymerase II molecule at the 5′ end of the uninduced hsp70 gene of D. melanogaster is transcriptionally engaged. Cell54, 795–804 (1988). ArticleCASPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Lis, J. Promoter-associated pausing in promoter architecture and postinitiation transcriptional regulation. Cold Spring Harb. Symp. Quant. Biol.63, 347–356 (1998). ArticleCASPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Brown, S. A., Imbalzano, A. N. & Kingston, R. E. Activator-dependent regulation of transcriptional pausing on nucleosomal templates. Genes Dev.10, 1479–1490 (1996). ArticleCASPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Brown, S. A., Weirich, C. S., Newton, E. M. & Kingston, R. E. Transcriptional activation domains stimulate initiation and elongation at different times and via different residues. EMBO J.17, 3146–3154 (1998). ArticleCASPubMedPubMed CentralGoogle Scholar

- Sullivan, E. K., Weirich, C. S., Guyon, J. R., Sif, S. & Kingston, R. E. Transcriptional activation domains of human heat shock factor 1 recruit human SWI/SNF. Mol. Cell. Biol.21, 5826–5837 (2001). ArticleCASPubMedPubMed CentralGoogle Scholar

- Petesch, S. J. & Lis, J. T. Rapid, transcription-independent loss of nucleosomes over a large chromatin domain at Hsp70 loci. Cell134, 74–84 (2008). ArticleCASPubMedPubMed CentralGoogle Scholar

- Boehm, A. K., Saunders, A., Werner, J. & Lis, J. T. Transcription factor and polymerase recruitment, modification, and movement on dhsp70 in vivo in the minutes following heat shock. Mol. Cell. Biol.23, 7628–7637 (2003). ArticleCASPubMedPubMed CentralGoogle Scholar

- Park, J. M., Werner, J., Kim, J. M., Lis, J. T. & Kim, Y. J. Mediator, not holoenzyme, is directly recruited to the heat shock promoter by HSF upon heat shock. Mol. Cell8, 9–19 (2001). ArticleCASPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Mason, P. B., Jr & Lis, J. T. Cooperative and competitive protein interactions at the Hsp70 promoter. J. Biol. Chem.272, 33227–33233 (1997). ArticleCASPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Yuan, C. X. & Gurley, W. B. Potential targets for HSF1 within the preinitiation complex. Cell Stress Chaperones5, 229–242 (2000). ArticleCASPubMedPubMed CentralGoogle Scholar

- Östling, P., Björk, J. K., Roos-Mattjus, P., Mezger, V. & Sistonen, L. Heat shock factor 2 (HSF2) contributes to inducible expression of hsp genes through interplay with HSF1. J. Biol. Chem.282, 7077–7086 (2007). ArticlePubMedCASGoogle Scholar

- Denegri, M. et al. Human chromosomes 9, 12, and 15 contain the nucleation sites of stress-induced nuclear bodies. Mol. Biol. Cell13, 2069–2079 (2002). ArticleCASPubMedPubMed CentralGoogle Scholar

- Jolly, C. et al. In vivo binding of active heat shock transcription factor 1 to human chromosome 9 heterochromatin during stress. J. Cell Biol.156, 775–781 (2002). ArticleCASPubMedPubMed CentralGoogle Scholar

- Alastalo, T.-P. et al. Formation of nuclear stress granules involves HSF2 and coincides with the nucleolar localization of Hsp70. J. Cell Sci.116, 3557–3570 (2003). ArticleCASPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Jolly, C. et al. Stress-induced transcription of satellite III repeats. J. Cell Biol.164, 25–33 (2004). ArticleCASPubMedPubMed CentralGoogle Scholar

- Rizzi, N. et al. Transcriptional activation of a constitutive heterochromatic domain of the human genome in response to heat shock. Mol. Biol. Cell15, 543–551 (2004). ArticleCASPubMedPubMed CentralGoogle Scholar

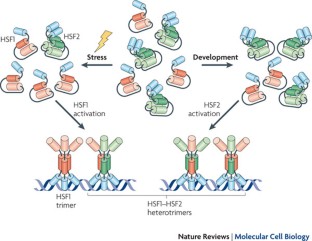

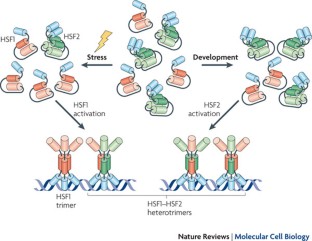

- Sandqvist, A. et al. Heterotrimerization of heat-shock factors 1 and 2 provides a transcriptional switch in response to distinct stimuli. Mol. Biol. Cell20, 1340–1347 (2009). Provides the first evidence of a functional interplay between HSFs through heterotrimerization.ArticleCASPubMedPubMed CentralGoogle Scholar

- Tanabe, M., Nakai, A., Kawazoe, Y. & Nagata, K. Different thresholds in the responses of two heat shock transcription factors, HSF1 and HSF3. J. Biol. Chem.272, 15389–15395 (1997). ArticleCASPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Fujimoto, M. et al. HSF4 is required for normal cell growth and differentiation during mouse lens development. EMBO J.23, 4297–4306 (2004). Shows that there is competition between distinct HSF family members for regulating FGF expression in the lens.ArticleCASPubMedPubMed CentralGoogle Scholar

- Jedlicka, P., Mortin, M. A. & Wu, C. Multiple functions of Drosophila heat shock transcription factor in vivo. EMBO J.16, 2452–2462 (1997). ArticleCASPubMedPubMed CentralGoogle Scholar

- Trinklein, N. D., Murray, J. I., Hartman, S. J., Botstein, D. & Myers, R. M. The role of heat shock transcription factor 1 in the genome-wide regulation of the mammalian heat shock response. Mol. Biol. Cell15, 1254–1261 (2004). ArticleCASPubMedPubMed CentralGoogle Scholar

- Takaki, E. et al. Maintenance of olfactory neurogenesis requires HSF1, a major heat shock transcription factor in mice. J. Biol. Chem.281, 4931–4937 (2006). ArticleCASPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Christians, E., Davis, A. A., Thomas, S. D. & Benjamin, I. J. Maternal effect of Hsf1 on reproductive success. Nature407, 693–694 (2000). ArticleCASPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Metchat, A. et al. Mammalian heat shock factor 1 is essential for oocyte meiosis and directly regulates Hsp90α expression. J. Biol. Chem.284, 9521–9528 (2009). Establishes a role for the maternal transcription factor HSF1 in the normal progression of meiosis in oocytes.ArticleCASPubMedPubMed CentralGoogle Scholar

- Bierkamp, C. et al. Lack of maternal heat shock factor 1 results in multiple cellular and developmental defects, including mitochondrial damage and altered redox homeostasis, and leads to reduced survival of mammalian oocytes and embryos. Dev. Biol.339, 338–353 (2010). ArticleCASPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Inouye, S. et al. Impaired IgG production in mice deficient for heat shock transcription factor 1. J. Biol. Chem.279, 38701–38709 (2004). ArticleCASPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Takii, R. et al. Heat shock transcription factor 1 inhibits expression of IL-6 through activating transcription factor 3. J. Immunol.184, 1041–1048 (2010). ArticleCASPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Santos, S. D. & Saraiva, M. J. Enlarged ventricles, astrogliosis and neurodegeneration in heat shock factor 1 null mouse brain. Neuroscience126, 657–663 (2004). ArticleCASPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Homma, S. et al. Demyelination, astrogliosis, and accumulation of ubiquitinated proteins, hallmarks of CNS disease in hsf1-deficient mice. J. Neurosci.27, 7974–7986 (2007). ArticleCASPubMedPubMed CentralGoogle Scholar

- Rallu, M. et al. Function and regulation of heat shock factor 2 during mouse embryogenesis. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA94, 2392–2397 (1997). ArticleCASPubMedPubMed CentralGoogle Scholar

- Kallio, M. et al. Brain abnormalities, defective meiotic chromosome synapsis and female subfertility in HSF2 null mice. EMBO J.21, 2591–2601 (2002). ArticleCASPubMedPubMed CentralGoogle Scholar

- Wang, G., Zhang, J., Moskophidis, D. & Mivechi, N. F. Targeted disruption of the heat shock transcription factor (hsf)-2 gene results in increased embryonic lethality, neuronal defects, and reduced spermatogenesis. Genesis36, 48–61 (2003). ArticleCASPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Chang, Y. et al. Role of heat-shock factor 2 in cerebral cortex formation and as a regulator of p35 expression. Genes Dev.20, 836–847 (2006). The first identification of a direct target gene of HSFs in development.ArticleCASPubMedPubMed CentralGoogle Scholar

- Tsai, L. H., Delalle, I., Caviness, V. S., Jr, Chae, T. & Harlow, E. p35 is a neural-specific regulatory subunit of cyclin-dependent kinase 5. Nature371, 419–423 (1994). ArticleCASPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Chae, T. et al. Mice lacking p35, a neuronal specific activator of Cdk5, display cortical lamination defects, seizures, and adult lethality. Neuron18, 29–42 (1997). ArticleCASPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Sarge, K. D., Park-Sarge, O.-K., Kirby, J. D., Mayo, K. E. & Morimoto, R. I. Expression of heat shock factor 2 in mouse testis: potential role as a regulator of heat-shock protein gene expression during spermatogenesis. Biol. Reprod.50, 1334–1343 (1994). ArticleCASPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Mendell, J. T. miRiad roles for the miR-17-92 cluster in development and disease. Cell133, 217–222 (2008). ArticleCASPubMedPubMed CentralGoogle Scholar

- Åkerfelt, M. et al. Promoter ChIP-chip analysis in mouse testis reveals Y chromosome occupancy by HSF2. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA105, 11224–11229 (2008). Provides a global description of HSF2 target genes in mouse testis.ArticlePubMedPubMed CentralGoogle Scholar

- Wang, G. et al. Essential requirement for both hsf1 and hsf2 transcriptional activity in spermatogenesis and male fertility. Genesis38, 66–80 (2004). ArticlePubMedCASGoogle Scholar

- Min., J. N., Zhang, Y., Moskophidis, D. & Mivechi, N. F. Unique contribution of heat shock transcription factor 4 in ocular lens development and fiber cell differentiation. Genesis40, 205–217 (2004). ArticleCASPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Shi, X. et al. Removal of Hsf4 leads to cataract development in mice through down-regulation of γS-crystallin and Bfsp expression. BMC Mol. Biol.10, 10 (2009). ArticlePubMedPubMed CentralCASGoogle Scholar

- Bu, L. et al. Mutant DNA-binding domain of HSF4 is associated with autosomal dominant lamellar and Marner cataract. Nature Genet.31, 276–278 (2002). The first study to link a mutation of an HSF gene to a particular disease.ArticleCASPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Fujimoto, M. et al. Analysis of HSF4 binding regions reveals its necessity for gene regulation during development and heat shock response in mouse lenses. J. Biol. Chem.283, 29961–29970 (2008). ArticleCASPubMedPubMed CentralGoogle Scholar

- Hsu, A. L., Murphy, C. T. & Kenyon, C. Regulation of aging and age-related disease by DAF-16 and heat-shock factor. Science300, 1142–1145 (2003). Establishes the link between HSF and the insulin-like signalling pathway in the regulation ofC. eleganslifespan.ArticleCASPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Morley, J. F. & Morimoto, R. I. Regulation of longevity in Caenorhabditis elegans by heat shock factor and molecular chaperones. Mol. Biol. Cell15, 657–664 (2004). Provides the first evidence for the important role of HSF and molecular chaperone networks in ageing.ArticleCASPubMedPubMed CentralGoogle Scholar

- Ben-Zvi, A., Miller, E. A. & Morimoto, R. I. Collapse of proteostasis represents an early molecular event in Caenorhabditis elegans aging. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA106, 14914–14919 (2009). Shows that failure in proteostasis occurs at an early stage of adulthood and coincides with a severely reduced activation of the heat shock response.ArticleCASPubMedPubMed CentralGoogle Scholar

- Bishop, N. A. & Guarente, L. Genetic links between diet and lifespan: shared mechanisms from yeast to humans. Nature Rev. Genet.8, 835–844 (2007). ArticleCASPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Heydari, A. R. et al. Effect of caloric restriction on the expression of heat shock protein 70 and the activation of heat shock transcription factor 1. Dev. Genet.18, 114–124 (1996). ArticleCASPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Lindquist, S. & Craig, E. A. The heat-shock proteins. Annu. Rev. Genet.22, 631–677 (1988). ArticleCASPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Morimoto, R. I. Regulation of the heat shock transcriptional response: cross talk between a family of heat shock factors, molecular chaperones, and negative regulators. Genes Dev.12, 3788–3796 (1998). ArticleCASPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Stringham, E. G. & Candido, E. P. Targeted single-cell induction of gene products in Caenorhabditis elegans: a new tool for developmental studies. J. Exp. Zool.266, 227–233 (1993). ArticleCASPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Prahlad, V. & Morimoto, R. I. Integrating the stress response: lessons for neurodegenerative diseases from C. elegans. Trends Cell Biol.19, 52–61 (2009). ArticleCASPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Clark, D. A., Gabel, C. V., Gabel, H. & Samuel, A. D. Temporal activity patterns in thermosensory neurons of freely moving Caenorhabditis elegans encode spatial thermal gradients. J. Neurosci.27, 6083–6090 (2007). ArticleCASPubMedPubMed CentralGoogle Scholar

- Mori, I. Genetics of chemotaxis and thermotaxis in the nematode Caenorhabditis elegans. Annu. Rev. Genet.33, 399–422 (1999). ArticleCASPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Prahlad, V., Cornelius, T. & Morimoto, R. I. Regulation of the cellular heat shock response in Caenorhabditis elegans by thermosensory neurons. Science320, 811–814 (2008). Introduces the concept that the heat shock response in somatic cells is not cell-autonomous, but depends on thermosensory neurons.ArticleCASPubMedPubMed CentralGoogle Scholar

- Tang, D. et al. Expression of heat shock proteins and heat shock protein messenger ribonucleic acid in human prostate carcinoma in vitro and in tumors in vivo. Cell Stress Chaperones10, 46–58 (2005). ArticleCASPubMedPubMed CentralGoogle Scholar

- Khaleque, M. A. et al. Heat shock factor 1 represses estrogen-dependent transcription through association with MTA1. Oncogene27, 1886–1893 (2008). ArticleCASPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Dai, C., Whitesell, L., Rogers, A. B. & Lindquist, S. Heat shock factor 1 is a powerful multifaceted modifier of carcinogenesis. Cell130, 1005–1018 (2007). Describes HSF1 as a non-oncogene that is required for tumour initiation and maintenance in various cancer models.ArticleCASPubMedPubMed CentralGoogle Scholar

- Whitesell, L. & Lindquist, S. Inhibiting the transcription factor HSF1 as an anticancer strategy. Expert Opin. Ther. Targets.13, 469–478 (2009). ArticleCASPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Westerheide, S. D. & Morimoto, R. I. Heat shock response modulators as therapeutic tools for diseases of protein conformation. J. Biol. Chem.280, 33097–33100 (2005). ArticleCASPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Westerheide, S. D. et al. Celastrols as inducers of the heat shock response and cytoprotection. J. Biol. Chem.279, 56053–56060 (2004). ArticleCASPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Trott, A. et al. Activation of heat shock and antioxidant responses by the natural product celastrol: transcriptional signatures of a thiol-targeted molecule. Mol. Biol. Cell19, 1104–1112 (2008). ArticleCASPubMedPubMed CentralGoogle Scholar

- Neef, D. W., Turski, M. L. & Thiele, D. J. Modulation of heat shock transcription factor 1 as a therapeutic target for small molecule intervention in neurodegenerative disease. PLoS Biol.8, e1000291 (2010). ArticlePubMedPubMed CentralCASGoogle Scholar

- Westerheide, S. D., Kawahara, T. L., Orton, K. & Morimoto, R. I. Triptolide, an inhibitor of the human heat shock response that enhances stress-induced cell death. J. Biol. Chem.281, 9616–9622 (2006). ArticleCASPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Phillips, P. A. et al. Triptolide induces pancreatic cancer cell death via inhibition of heat shock protein 70. Cancer Res.67, 9407–9416 (2007). ArticleCASPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Amin, J., Ananthan, J. & Voellmy, R. Key features of heat shock regulatory elements. Mol. Cell. Biol.8, 3761–3769 (1988). CASPubMedPubMed CentralGoogle Scholar

- Xiao, H. & Lis, J. T. Germline transformation used to define key features of heat-shock response elements. Science239, 1139–1142 (1988). ArticleCASPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Perisic, O., Xiao, H. & Lis, J. T. Stable binding of Drosophila heat shock factor to head-to-head and tail-to-tail repeats of a conserved 5 bp recognition unit. Cell59, 797–806 (1989). ArticleCASPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Xiao, H., Perisic, O. & Lis, J. T. Cooperative binding of Drosophila heat shock factor to arrays of a conserved 5 bp unit. Cell64, 585–593 (1991). ArticleCASPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Gorisch, S. M., Lichter, P. & Rippe, K. Mobility of multi-subunit complexes in the nucleus: accessibility and dynamics of chromatin subcompartments. Histochem. Cell Biol.123, 217–228 (2005). ArticlePubMedCASGoogle Scholar

- Cotto, J., Fox, S. & Morimoto, R. HSF1 granules: a novel stress-induced nuclear compartment of human cells. J. Cell Sci.110, 2925–2934 (1997). ArticleCASPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Chiodi, I. et al. Structure and dynamics of hnRNP-labelled nuclear bodies induced by stress treatments. J. Cell Sci.113, 4043–4053 (2000). ArticleCASPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Denegri, M. et al. Stress-induced nuclear bodies are sites of accumulation of pre-mRNA processing factors. Mol. Biol. Cell12, 3502–3514 (2001). ArticleCASPubMedPubMed CentralGoogle Scholar

- Metz, A., Soret, J., Vourc'h, C., Tazi, J. & Jolly, C. A key role for stress-induced satellite III transcripts in the relocalization of splicing factors into nuclear stress granules. J. Cell Sci.117, 4551–4558 (2004). ArticleCASPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Weighardt, F. et al. A novel hnRNP protein (HAP/SAF-B) enters a subset of hnRNP complexes and relocates in nuclear granules in response to heat shock. J. Cell Sci.112, 1465–1476 (1999). ArticleCASPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Chiodi, I. et al. RNA recognition motif 2 directs the recruitment of SF2/ASF to nuclear stress bodies. Nucleic Acids Res.32, 4127–4136 (2004). ArticleCASPubMedPubMed CentralGoogle Scholar

- Valgardsdottir, R. et al. Structural and functional characterization of noncoding repetitive RNAs transcribed in stressed human cells. Mol. Biol. Cell16, 2597–2604 (2005). ArticleCASPubMedPubMed CentralGoogle Scholar

- Shinka, T. et al. Molecular characterization of heat shock-like factor encoded on the human Y chromosome, and implications for male infertility. Biol. Reprod.71, 297–306 (2004). ArticleCASPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Tessari, A. et al. Characterization of HSFY, a novel AZFb gene on the Y chromosome with a possible role in human spermatogenesis. Mol. Hum. Reprod.10, 253–258 (2004). ArticleCASPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Bhowmick, B. K., Takahata, N., Watanabe, M. & Satta, Y. Comparative analysis of human masculinity. Genet. Mol. Res.5, 696–712 (2006). PubMedGoogle Scholar

- Thompson, J. D., Higgins, D. G. & Gibson, T. J. CLUSTAL W: improving the sensitivity of progressive multiple sequence alignment through sequence weighting, position-specific gap penalties and weight matrix choice. Nucleic Acids Res.22, 4673–4680 (1994). ArticleCASPubMedPubMed CentralGoogle Scholar

- Sistonen, L., Sarge, K. D. & Morimoto, R. I. Human heat shock factors 1 and 2 are differentially activated and can synergistically induce hsp70 gene transcription. Mol. Cell. Biol.14, 2087–2099 (1994). CASPubMedPubMed CentralGoogle Scholar

Acknowledgements

We apologize to our colleagues whose original work could only be cited indirectly owing to space limitations. Members of our laboratories are acknowledged for valuable comments on the manuscript. Our own work is supported by The Academy of Finland, The Sigrid Jusélius Foundation, The Finnish Cancer Organizations and Åbo Akademi University. The image in box 2 is courtesy of A. Sandqvist, Department of Biosciences, Åbo Akademi University, Turku, Finland.